Marginal Utility and Diminishing Returns in Real Life Economics

Economics runs on a simple idea that keeps proving itself in daily life. The first slice of pizza tastes great. The second still hits the spot. By the fourth, you start questioning your choices. That slide from “great” to “fine” to “I’m good” is not a mood swing. It is the core pattern that links how people value extra units of anything to how firms scale output on a factory floor. The terms are marginal utility on the consumer side and diminishing returns on the production side. Get both right and you can explain demand curves, price moves, promotions, capacity planning, cost curves, and the logic behind a surprising number of policy debates. This chapter builds the theory with plain math, connects it to behavior, and turns it into field tactics students can use for real planning.

Total utility and marginal utility in plain language

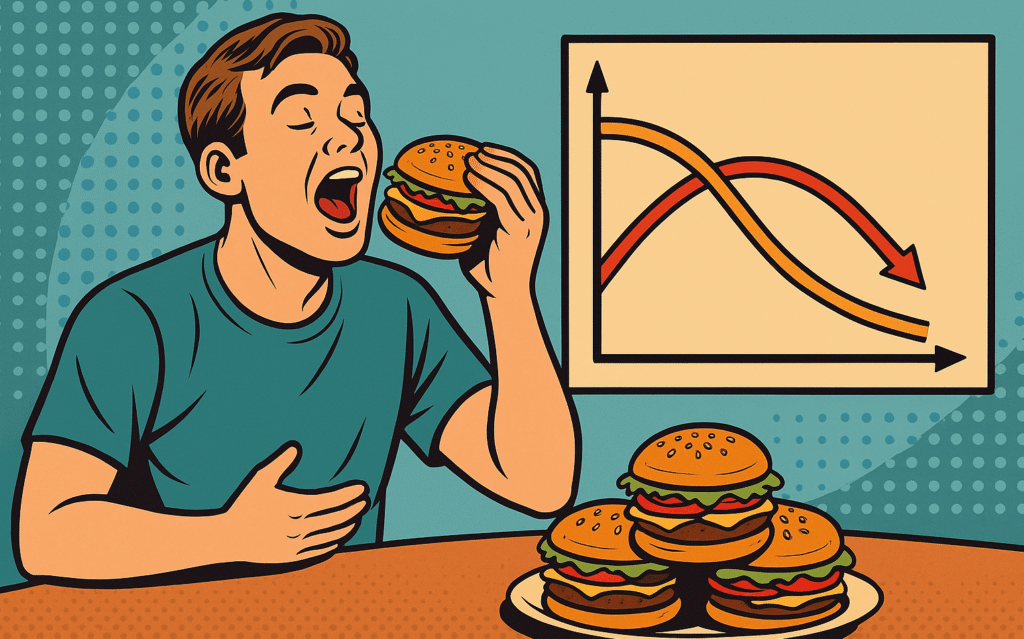

Start with two definitions. Total utility is the overall satisfaction from consuming a given quantity of a good or service in a given period. Marginal utility is the extra satisfaction from one more unit. If total utility rises from 40 to 46 when you go from three to four slices, the marginal utility of that fourth slice is 6. The law that shows up again and again is diminishing marginal utility. As quantity consumed rises within a short window, the added satisfaction from one more unit usually falls. That does not mean total utility falls right away. It can keep rising while each extra unit adds less than the one before. The pattern holds for most goods because needs get filled, tastes saturate, and time is limited.

The exceptions prove the rule. A hobby that clicks can show increasing marginal utility at the start while you learn the basics. After a while, the curve bends down as skill plateaus and novelty fades. For addictive goods, the curve can be messy in the short run. In the long run, physical limits and opportunity cost pull you back toward diminishing marginal utility. If you remember one sentence, make it this. The extra from an extra unit falls once the main need is met.

The demand curve lives inside marginal utility

Demand curves slope downward because marginal utility usually falls with quantity. A buyer pays up for the first unit because it tackles the most urgent use. Additional units handle less urgent uses and are worth less. Translate that logic into price willingness. The maximum price you would pay for a unit equals the marginal utility of that unit measured in money. As quantity rises, that willingness to pay falls, so the demand curve slopes down. This is not just theory. It is the backbone of pricing in every sector from snacks to software.

Two practical notes follow. First, time matters. Spread the same quantity across more days and your marginal utility schedule can shift up because the rush of saturation fades between uses. Second, context matters. Pairing goods changes marginal utility. A phone without a charger has low utility. With a charger and a data plan, the package delivers far more. Product managers build around this complementarity, which is why bundles exist.

Ordinal preferences and the indifference curve toolkit

Classical texts once treated utility as a number you could add and subtract. Modern work relies on ordinal preferences. You do not need to attach numbers to utility. You only need to rank bundles. If bundle A beats bundle B in your ranking, you prefer A. Plot combinations of two goods that you like equally and you draw an indifference curve. The slope of that curve at a point is the marginal rate of substitution, which shows how much of good Y you would give up for one more unit of good X while staying on the same satisfaction level. Diminishing marginal utility gives the indifference curve its bowed shape. As you hold more of good X, you give up less of Y for another unit of X because X is delivering smaller extra gains at the margin.

Put a budget line on the same chart. Its slope equals the relative price. The consumer’s best attainable bundle sits where the budget line is just tangent to the highest reachable indifference curve. At that point the marginal rate of substitution equals the price ratio. Translated to words you can use in a briefing, the consumer has balanced the extra satisfaction per money unit across goods. Any deviation would lower satisfaction or break the budget.

Equi-marginal rule across many goods

Scale up from two goods to many and a powerful rule appears. A consumer maximizes satisfaction by allocating spending such that the marginal utility per unit of currency is equalized across all goods. If the marginal utility per krona is higher for apples than for oranges, shift a unit of spending from oranges to apples. Keep shifting until the bang for the buck is equal everywhere that matters. Price changes knock the system out of balance and trigger a new allocation. This rule is how households stretch money without writing equations. Firms imitate it across channels, balancing marginal return per dollar of outlay on ads, staff hours, or shelf space.

Diminishing marginal utility of income and why it matters

Zoom out from goods to money itself. For most people additional income raises well-being, but each added unit raises it by less than the previous one. That pattern is called diminishing marginal utility of income. It is why a small unexpected cost hits a low income household much harder than it hits a high income one. It is also why risk protection that smooths bad outcomes has value even if the average payout equals the premium in raw money terms. The extra money in bad states is worth more in utility than the same money in good states is worth. Students can translate this into real behavior. Building a small cash buffer raises peace of mind because the first few thousand cover emergencies with very high marginal value.

Behavioral twists without breaking the core rule

Humans show habits that bend the clean graph at the edges. Present bias leads people to overweight immediate pleasure and underweight later pain. Marginal utility can look high in the short window even though it will look low when the bill arrives next month. Reference dependence means people judge gains and losses relative to a benchmark, not absolute levels. A coffee priced one krona below a round anchor can feel like a win out of proportion to the tiny money value. Variety seeking rotates choices even when a single option would score highest on average. None of these break the main logic. They explain why marginal utility measured today can move around with framing and timing. Good design helps people pick the option they will still like tomorrow.

From utility to market metrics – consumer surplus and willingness to pay

Policy analysts and product teams care about the area between what buyers would have paid and what they actually pay. That area is consumer surplus. It is the sum across units of the gap between willingness to pay and price. Diminishing marginal utility makes the area finite and makes price changes affect surplus in a predictable way. A price cut transfers some value from the seller to buyers and adds new trades that never would have happened at the old price. A price increase does the opposite. If you can sketch the demand curve and know volumes, you can estimate how much value a promotion created or destroyed. That skill separates hand waving from solid planning.

Diminishing returns on the production side

Switch to firms. Diminishing returns describes the short run pattern when one input is fixed and you add more of a variable input. Imagine a workshop with a fixed number of machines. Add workers. At first, output rises quickly because idle time falls and coordination improves. Add more and the workshop gets crowded. Workers wait for machines. Communication delays build. Output still rises, but each additional worker adds less to total output than the one before. That is diminishing marginal product.

Three curves keep showing up in textbooks for a reason. Total product rises then flattens as crowding grows. Marginal product rises early then falls as congestion appears. Average product rises while marginal product sits above it and falls once marginal product drops below it. The pattern is not picky about the input. It shows up for labor given fixed equipment. It shows up for fertilizer given fixed land. It shows up for ad spend given fixed attention from a target audience. At some point the channel saturates and every extra unit buys less response.

Diminishing returns and cost curves

Tie the production story to costs. If marginal product falls, then marginal cost rises for each additional unit of output, because you need more of the variable input to squeeze out each extra unit when the fixed factor is binding. That gives the familiar U shape for marginal and average variable cost in the short run. Early units are cheap because the team uses idle capacity well. Later units become costly as overtime kicks in and bottlenecks bite. Pricing and output choices need to respect this shape. A flash sale that pushes volume past the sweet spot can raise unit cost and crush margin, even if revenue looks flashy. Smart teams know their capacity band, steer orders into that lane, and price delivery speed separately when demand spikes.

Returns to scale versus diminishing returns

Two ideas get mixed up all the time. Diminishing returns is a short run concept with at least one input fixed. Returns to scale is a long run concept where all inputs can change. Double every input and ask what happens to output. If output more than doubles, that is increasing returns to scale, often due to specialization, learning, or network effects. If output doubles exactly, that is constant returns to scale. If output less than doubles, that is decreasing returns to scale, often due to management stretch or congestion at levels that no process can entirely avoid. A factory can show diminishing marginal product of labor today because machines are fixed, while the same factory can show increasing returns to scale over years as it adds lines, automates, and learns better methods. Keep the time frame clear and you will not trip.

Isoquants, marginal rate of technical substitution, and cost minimization

Firms pick input combinations that produce target output at the lowest cost. Plot isoquants, which are combinations of labor and capital that yield the same output. The slope of an isoquant is the marginal rate of technical substitution. It shows how much capital you can give up for one more unit of labor while holding output constant. The cost side appears as isocost lines. The firm’s cost minimum for a given output sits where an isoquant is tangent to an isocost. The condition is simple to state. The ratio of marginal products equals the ratio of input prices. If an extra hour of labor adds less output per krona than a unit of capital does, shift spending toward capital. Diminishing marginal product gives isoquants their curved shape and ensures a neat interior solution rather than a corner where the firm uses only one input.

Learning curves and why diminishing returns is not the whole story

Production teams improve with experience. The learning curve says cost per unit falls by a fixed percentage every time cumulative output doubles. That trend can offset diminishing returns for a while. Early in a program, each extra unit teaches something that lowers cost for the next batch. After years of refinement, learning slows, and the familiar diminishing returns on intensive use of a fixed factor reappear in day to day operations. This mix explains real factories. They show long run cost declines across generations of products while still facing short run congestion if a specific line is pushed beyond its comfortable range in a given week.

Saturation, variety, and the demand side mirror of diminishing returns

Products face diminishing returns in demand not only because of fatigue but because buyers seek variety. The law of diminishing marginal utility for a single good pushes consumers toward portfolios of goods. After a point, the extra utility from more of good A is lower than the extra utility from a little of good B. That is why retailers rotate promotions across categories and why content platforms allocate slots across genres. The marginal utility of any single line falls with exposure, so the bundle must change to keep the average high. Understanding this rhythm helps teams plan calendars that do not burn out their audience.

Price discrimination and quantity discounts through the lens of marginal utility

Firms try to match price to willingness to pay. Diminishing marginal utility gives a clean rationale for quantity discounts and two part pricing models. The first unit is worth more to the buyer than later units, so a lower per unit price for larger bundles can raise participation and total surplus. Two part pricing charges a fixed access fee plus a per unit price that can sit close to marginal cost. The access fee captures part of the value of early units with high marginal utility, while the low per unit price keeps later units flowing. The details require care and honest constraints, but the foundation is the same. Buyers value early units more than late units, and pricing that respects that pattern does better than one flat rate.

Promotions, sampling, and the marginal utility of information

Consumers do not know their own utility schedules for new goods until they try them. The marginal utility of information can be high for the first unit because it resolves uncertainty. Free trials, samples, and intro pricing exploit that. Once information lands, the utility schedule for the good stabilizes and pricing can adjust. Beware the trap of training customers to wait for discounts. If you run promotions too often, the marginal utility of buying at full price plummets because the expected deal sits just ahead. The first rule of promotions is to protect the premium segments that still show high willingness to pay for early units.

Diminishing returns in teams and time management

Economics shows up in calendars. The first focused hour on a hard task delivers big progress. The fourth consecutive hour delivers less. Breaks reset the curve by moving you back to a range where marginal productivity rises again. Teams show the same rhythm. The third person on a small project adds a lot. The ninth can slow things down with extra coordination. Leaders use that reality when scoping work. Staff to the point where marginal contribution still beats the marginal coordination cost. Add people in layers with clear interfaces and you keep marginal returns healthy rather than watching them collapse under meetings.

Policy links without jargon

Several policy lines draw directly from diminishing marginal utility and diminishing returns. A small fee on congestion raises big gains because the marginal social cost of an extra car during the peak is high. A well targeted subsidy for first doses of a vaccine raises coverage among groups where the marginal utility of protection is high but barriers are real. Support for early childhood programs yields large returns because skills compound and later remediation shows diminishing returns. On the firm side, incentives for basic research work because early findings have large spillovers while late stage copycat spending often shows diminishing returns. The common thread is to push resources where marginal gains per unit are still strong.

Field diagnostics you can run without fancy tools

If you want to make these ideas useful tomorrow, train your eye for three patterns. First, look for saturation on the demand side. Track unit usage by cohort over time. If the curve flattens, marginal utility is falling faster than you planned, and it is time to adjust packaging or rotate features. Second, watch throughput against capacity on the supply side. If lead times jump and defect rates rise, you have hit diminishing returns from a fixed bottleneck. Expand the fixed factor or pull volume back inside the sweet spot. Third, compare marginal gains across options before throwing resources at a problem. If the next euro on Channel A yields less than the next euro on Channel B, rebalance now rather than waiting for quarter end. That habit is the equi-marginal rule in action.

Worked numerical sketch that locks in the idea

Say a student values cups of tea this hour with marginal utilities of 10, 7, 5, 3, and 1 in money units. The price per cup is 4. The first cup beats price by 6, the second by 3, the third by 1, the fourth falls short by 1. The student buys three cups. Total surplus from tea is 10 minus 4 plus 7 minus 4 plus 5 minus 4, which equals 10. Now drop price to 3. The fourth cup clears with a margin of 0. Total surplus rises. Raise price to 6 and only the first cup clears. These tiny numbers carry large lessons. Demand slopes down because later units deliver less. Prices that sit near the margin decide how many units move. Promotions that push price down for a while unlock units with modest marginal utility that would never have moved otherwise.

Shift to production. A shop with one press adds workers. Output by worker added is 12, 10, 7, 5, and 3 units per day. If the wage is fixed per worker per day, marginal cost per extra unit rises as the marginal product falls. Pricing a rush order without checking where you sit on that curve is how projects turn into red ink. Run the numbers before you quote. That is not rocket science. It is operational discipline.

Common pitfalls and how to avoid them

Do not assume diminishing marginal utility means total utility falls after a few units. It usually keeps rising for a while, just more slowly. Do not confuse one person’s utility slide with another’s. Heterogeneity is real. Some people get more from the third hour at the gym than others get from the first. Do not mix up diminishing returns with decreasing returns to scale. One is about a fixed factor in the short run. The other is about scaling all inputs in the long run. Finally, do not treat a promotion bump as proof that more volume forever is good. You may have pulled demand forward and pushed operations into the costly zone. Check cohort retention and unit economics at the new level before calling victory.

A short glossary you will actually use

Total utility is satisfaction from a given quantity.

Marginal utility is the extra satisfaction from one more unit.

Law of diminishing marginal utility says that extra satisfaction usually falls as quantity rises in a short window.

Indifference curve shows bundles a person values equally.

Marginal rate of substitution is the trade between two goods that keeps satisfaction flat.

Equi-marginal rule balances marginal utility per currency unit across goods.

Marginal product is the extra output from one more unit of an input with others fixed.

Law of diminishing returns says marginal product falls when a variable input rises with at least one fixed input.

Marginal cost is the extra cost of one more unit of output.

Returns to scale describes how output changes when all inputs scale together.

Consumer surplus is the difference between willingness to pay and price summed across units.

Pin those terms and the rest of the chapter will snap into place during review.

Wrapping It Up

Treat the next unit as the only unit that matters for decisions. On the demand side, ask whether the extra unit a buyer might take still brings enough joy to clear the price, then set packaging and price so early units are easy and later units are fair. On the supply side, run capacity bands and keep orders inside the range where marginal cost behaves. Balance outlays so the next euro in each channel returns roughly the same gain. Watch for saturation, seasonal resets, and learning effects that shift curves over time. And keep your playbooks boring. Old school blocking and tackling beats guesswork.

Marginal utility and diminishing returns are not trivia for exams. They are the backbone that turns scattered preferences and finite capacity into clean calls on pricing, staffing, promotions, and timing. Learn to see the slope at the margin and you will sound like the adult in the room the next time a plan gets stretched just because “more must be better.”