Game Theory – Strategy, Payoffs, Nash Equilibrium & Real-World Games

Game theory studies strategic interaction. Your outcome depends on what others do and their outcome depends on you. That simple fact sits behind pricing moves, wage talks, patent races, trade disputes, stand-offs, and even study groups. Learn the vocabulary and the standard playbooks and you can model a situation before you are in it, stress test your plan, and nip bad habits that keep teams stuck.

Players, strategies, and payoffs

Every game has players, strategies, and payoffs. A player is any decision maker who can choose among actions. A strategy is a full plan that specifies what a player will do in every situation that could arise. A payoff is the reward or penalty associated with the outcome. In business class exercises the reward is often a number that stands in for profit or utility. In policy and everyday life the reward can be votes, time saved, reputational credit, or avoided pain.

Two standard blueprints organize games. The normal form puts choices in a matrix so you can read best responses off the rows and columns. The extensive form draws a decision tree with nodes that show who moves when and what each player knows at that point. The normal form helps with static interactions where choices land at once or where timing does not change incentives. The extensive form captures threats, promises, and the credibility of each move.

Dominance is the fastest filter. If one action gives a player a payoff at least as good in every scenario and strictly better in some, it strictly dominates the other action. Rational players do not choose dominated strategies. Iterating that logic across all players often shrinks the game to a simpler core. If nothing is dominated you move to equilibrium concepts.

Nash equilibrium and best responses

A Nash equilibrium is a list of strategies, one for each player, where every strategy is a best response to the others. No single player can do better by deviating alone. In some games there is one equilibrium. In others there are many. In some there is no equilibrium in pure strategies and the solution requires mixing across actions with probabilities that keep opponents indifferent.

You find equilibria by writing best response functions and looking for mutual consistency. In matrix games you underline the best payoffs in each row and column and search for cells where both players are playing best responses at the same time. In continuous strategy games you set first order conditions and solve for fixed points. The math looks fancy in textbooks. The logic is simple. Keep what you would not regret after you see what the other side did.

Nash is a stability condition not a fairness doctrine. Some equilibria are efficient. Some waste potential gains because players cannot coordinate on a better outcome or because hidden information blocks cooperation. Knowing the difference lets you design institutions that shift the game.

Mixed strategies and why unpredictability pays

If your best move depends on what the other side does and they can read your patterns, predictability becomes a liability. A mixed strategy assigns probabilities to actions. In equilibrium the mix leaves opponents indifferent among the actions they could take in response. That indifference is the point. Your randomness removes exploitable edges.

Sports give clean examples. A soccer kicker alternates corners so the keeper cannot cheat. A pitcher varies fastballs and off-speed throws to keep a hitter off balance. Neither wants true randomness without feedback. They want enough unpredictability to destroy a pattern detector while still leaning on their strengths. In business settings a mixed strategy might be a rotation of promotional timing or a bidding tactic that sometimes sits out to cool a price war.

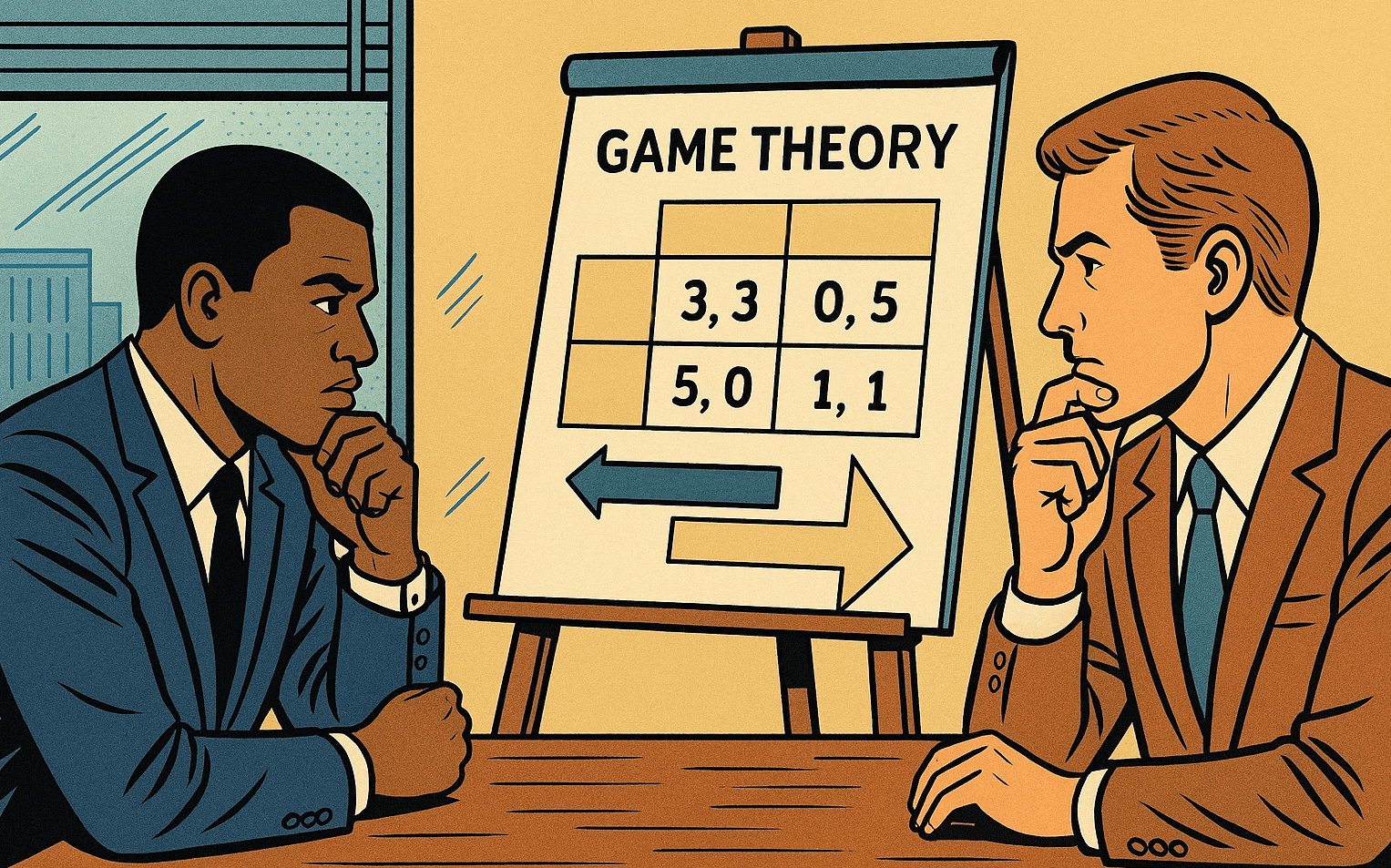

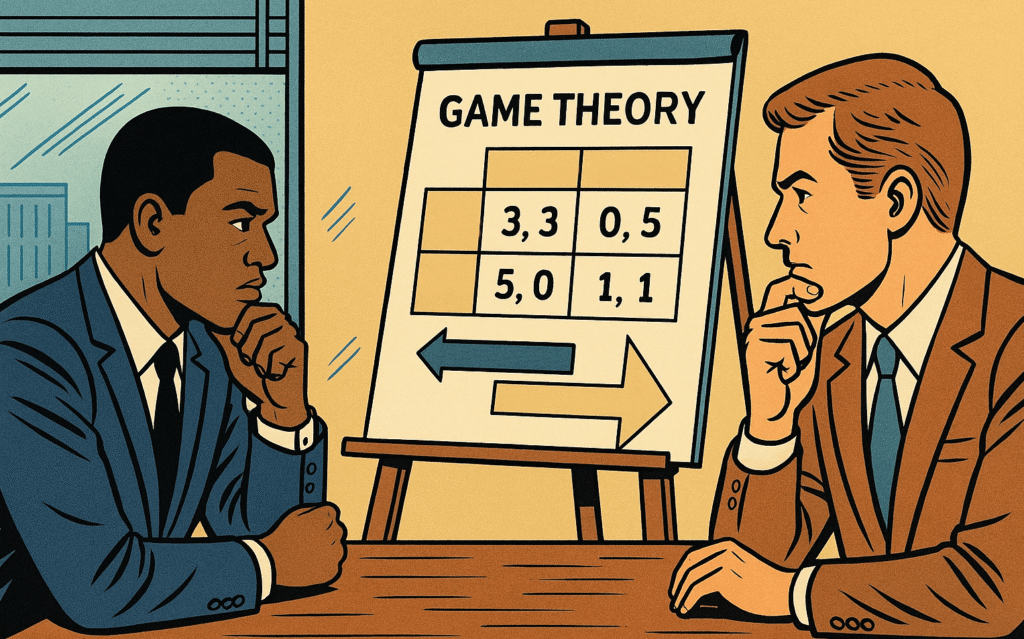

Prisoner’s Dilemma and the logic of defection

The most famous game is a two player setup with two actions each. Cooperate or defect. Mutual cooperation gives a good outcome to both. Mutual defection gives a worse outcome to both. If one cooperates while the other defects, the defector gets the best individual payoff and the cooperator gets the worst. Because defection yields a better result no matter what the other does, defect is a dominant strategy for each player. The Nash equilibrium is mutual defection. The pair leaves gains on the table.

You see this in price fixing attempts that unravel without enforcement, in study groups where each person hopes others do the hard work, and in CO₂ abatement where every country prefers others to cut more. The cure is not speeches about goodwill. The cure is a mechanism that changes incentives. Repeated interaction with credible punishment for cheating. Monitoring that raises the chance that cheating is caught. Side payments that reward cooperation. Rules with teeth.

Coordination, assurance, and the problem of multiple equilibria

Not all conflicts are zero-sum. Sometimes players want to coordinate but need help choosing the same outcome. Think of tech standards or driving on one side of the road. These games have multiple Nash equilibria. Everyone prefers to match the crowd rather than split. History and expectations decide which equilibrium wins. A focal point such as a widely known standard can push players into alignment.

Assurance games are a special case. Players prefer the high cooperation outcome if they trust that others will show up. Without trust they choose a safe low payoff action. The lesson for policy and management is practical. Publish commitments, stage early wins, and give signals that reduce doubt. Small assurances can unlock the better equilibrium when preferences already line up.

Chicken and brinkmanship

In Chicken each player prefers to stand firm while the other yields. The worst outcome is collision. There are two pure equilibria where one yields and the other stands firm. There is also a mixed equilibrium where each side takes risk. Players try to raise credibility by limiting their own options. Think of leaders who throw away the steering wheel to show commitment or firms that sign long supply contracts that lock them into a path. These tactics increase the chance the other side yields but also raise the risk of a crash. Use with care. Reputation is at stake and so is your margin for error.

Zero-sum games and minimax logic

A zero-sum game sets one player’s gain equal to the other’s loss. Poker is close within a table after rake. Many competitive exams and rankings also feel like this when seats are fixed. The central result says that each player has a value they can guarantee through a minimax strategy. They choose the mix that minimizes their maximum possible loss while the opponent chooses the mix that minimizes your payoff. Solving for those mixes can be done with linear programming or with simple algebra in small matrices.

Zero-sum logic is stark. You cannot both walk away happier except through side deals or by growing the pie with more entrants or new rules. The right mindset is discipline. Avoid patterns that let others read you and choose the strategy that locks in your floor.

Subgame perfection and credible threats

Some strategies look strong on paper and weak in execution because they rely on threats that will not be carried out when the time arrives. Subgame perfect equilibrium deletes those fairy tales. It requires optimal play in every subgame that could unfold. You find it by backward induction on the decision tree. Start at the end and roll back. Anything that depends on a threat you would not actually execute will not survive.

This is where commitment devices matter. If you can bind your future self you can change the current game. Automatic price matching that triggers a response without a meeting. A published return policy that avoids haggling. A labor contract that lays out steps instead of relying on ad hoc discretion. Commitments can be costly but they convert talk into structure.

Incomplete information and Bayesian games

Many real interactions involve private information. A bidder knows their valuation. A firm knows its cost. A regulator knows their willingness to enforce. When types are hidden you move from Nash equilibrium to Bayesian Nash equilibrium. Each player has beliefs about other players’ types and chooses a strategy that maximizes expected payoff given those beliefs and the strategies of others.

Signals and screens are the tools. A strong firm can send a costly signal that weak firms would avoid. Think of a long warranty from a producer with low defect rates. A buyer can design a screening menu that induces self selection. Think of contracts that trade price against flexibility so high value customers reveal themselves by choosing tighter terms. The numbers may feel abstract at first. The core idea is simple. Use actions that separate types so your counterpart reveals information through choice.

Signaling games and separating equilibria

A signaling game has a sender with private type and a receiver who chooses an action after seeing a signal. The sender’s cost of signaling differs by type. In a separating equilibrium different types choose different signals so the receiver learns the type and responds accordingly. In a pooling equilibrium all types send the same signal so the receiver relies on prior beliefs. Education as a signal of ability is the classic example studied in courses. In markets you also see costly certifications, money back guarantees, and public commitments to quality standards. Effective signals share two features. They are hard for low quality senders to mimic and valuable for high quality senders to use.

Cheap talk and strategic communication

Sometimes signals are costless words. That is cheap talk. Words can still move outcomes when players share some common interest and when lies can be punished indirectly over time. Firms pre-announce features to shape expectations. Central banks guide markets with forward statements. Partners in a group project set expectations in a kickoff meeting. Cheap talk works when listeners can verify later and adjust cooperation or trust. Without that feedback loop cheap talk is noise.

Auctions as applied game theory

Auctions are games with rules that map bids into allocations and payments. First price sealed bid auctions make the winner pay their bid. Second price sealed bid auctions make the winner pay the highest losing bid. English auctions raise price until only one bidder remains. Dutch auctions start high and drop until someone accepts. With private independent values and standard assumptions, truthful bidding is optimal in second price auctions because your bid only decides whether you win not what you pay. In first price auctions bidders shade down to leave surplus if they win. With common values and uncertain quality you face the winner’s curse because the highest bid is likely above the true value. Correcting for that requires discipline and good due diligence. The rule of thumb is to cool your bid when your signal is noisy and when the number of rivals is large.

Mechanism design in plain language

Mechanism design flips the game around. Instead of optimizing within rules you design rules that lead self interested players to produce the outcome you want. The task is to set up a game where the best move for each player is to tell the truth and take the action that supports the social goal. Two constraints drive the design. Incentive compatibility makes honesty the best policy. Participation makes joining voluntary. Classic tools include Vickrey auctions that reward truth telling, matching markets that avoid blocking pairs, and tax or transfer rules that elicit honest income reporting. The moral is practical. If you are always fighting with participants to behave, redesign the rules so cooperation aligns with self interest.

Matching markets and stable outcomes

College admissions, residency assignments, and public school choice are not best handled by prices alone. They are matching problems with preferences on both sides. The Gale-Shapley deferred acceptance algorithm produces a stable matching where no pair would both prefer to be matched with each other rather than their current partners. Stability matters because unstable systems invite side deals and constant churn. In hiring programs and school placements the algorithmic approach is not about fancy math. It is about cutting chaos and favoritism while giving applicants a clear path.

Bargaining and the value of time

Two players dividing a pie illustrate bargaining logic. If both want a deal and waiting is costly, there is a unique outcome in the standard alternating offers model with discounting. The side with more patience and better outside options secures a larger share. That is why deadlines matter and why you should always cultivate outside options. Write that into your preparation. Boost your alternative plans and improve your staying power. Now the same logic applies to wage talks, licensing negotiations, and partnership terms. Do not obsess over the first offer. Calibrate patience and outside options and the final split will move.

Repeated games, triggers, and reputation

Repeat a game and the strategy set explodes. Cooperation can become sustainable even when one-shot play predicts defection. The ingredients are shadow of the future, ability to monitor behavior, and credible punishment for deviations. Trigger strategies like grim or tit for tat can support high cooperation if players value the future enough. Real life is messy so forgiving strategies that punish and then reset often do better than permanent punishment. Reputation adds another layer. A player who becomes known for following through on punishments or for honoring deals can shift expectations and improve outcomes. Be careful though. An angry reputation can trap you into costly fights. A reputation for fairness with teeth often travels farther.

Public goods and free riding as a multiplayer game

Public goods provide value to everyone in a group once they exist. Contributions are costly and the temptation is to ride on others. The Nash equilibrium in simple models underproduces the good because each person ignores the benefit to others. Tools to fix this are aligned with game theory. Use matching contributions to raise the return to each unit given by individuals. Use rules that tie club benefits to contribution. Use repeated interactions with clear reputations to reward givers and sideline riders. If you can measure contributions and outcomes, design a mechanism that pays for verified delivery rather than relying on speeches.

Contests and all pay games

In a contest many players spend resources to increase their chance of winning a prize. An all pay auction is a sharp version where everyone pays their bid but only one gets the prize. Think of patent races or lobbying battles. Equilibrium bids often spend away a big chunk of the prize value. That is why leadership should avoid internal contests that burn hours without raising output. If you must run a contest, cap effort, set clear criteria, and make some rewards proportional to measurable output rather than winner take all.

Behavioral game theory and real humans

Standard models assume flawless calculation and stable preferences. People bring loss aversion, fairness concerns, and limited attention to the table. They reject low offers in ultimatum games even though a tiny gain beats zero. They punish defectors at a cost to themselves. They anchor on round numbers and ignore small probabilities. You do not need to memorize every bias to be effective. Build guardrails that make good behavior easy and bad behavior hard. Pre-commit to rules. Use defaults that favor cooperation. Add friction to moves that risk a spiral. Give feedback with clear dashboards so people see the link between choices and outcomes.

Price wars, entry deterrence, and credible capacity

Game theory demystifies standard market tactics. Predatory pricing fails as a general plan because it burns cash now for uncertain dominance later, yet price cuts can be rational if they reveal lower costs or if they shift beliefs about future toughness. Entry deterrence through capacity expansion can work when excess capacity is visible and costly to reverse, because it commits the incumbent to a strong response. Cheap talk that promises a fight without costly commitment does not move entrants. If you want a peaceful market, sometimes the smartest move is to accept a fair split early and keep credibility for non-aggression through transparent policies and responsive but not explosive play.

Trade policy and strategic tariffs

Tariffs shift payoffs across countries and across firms. A large buyer can sometimes push trading partners into better terms by threatening limited access, but retaliation and supply chain redesign can blunt the move. Strategic trade models show how subsidies or tariffs might support a national champion in a market with a few global players, yet the details matter. Without high certainty about technology and demand you risk a race that burns taxpayer money. The practical lesson is not to swing wildly. Use data on elasticities and rival responses and prefer tools that build capability rather than count on others folding.

Information design and what you reveal on purpose

Sometimes you can choose what information gets released. A platform can show averages rather than full distributions. A company can publish forward guidance in ranges rather than point estimates. A regulator can design disclosure rules that improve matching without sparking herding. Information design studies which signals produce the best outcomes given strategic reactions. The simple rule is to share enough to coordinate good behavior while guarding details that invite exploitation or short-termism. If disclosure invites a stampede, adjust the format. If secrecy breeds distrust and rumors, share more and set bright lines.

Commitment, contracts, and the power of structure

Contracts are device boxes. They turn threats and promises into enforceable steps. Liquidated damages clauses change the game by raising the cost of defection. Option clauses let a party expand cooperation once trust is proven. Automatic renewals with performance triggers reduce renegotiation risk. Escrow ties payments to verified milestones so neither side carries all the risk at once. People talk about win-win outcomes a lot. Contracts are how you get there and stay there without mythology.

How to model a real situation without theatrics

Start by defining players and feasible actions. Map information at each move. Write payoffs in relative terms if exact numbers are fuzzy. Look for dominated actions and delete them. Check for pure strategy equilibria. If none exist, consider mixed play. If the situation repeats, ask whether a trigger strategy could sustain cooperation and whether monitoring is possible. If information is private, think about incentives for truth telling and whether a screening menu could work. If the problem is coordination, standardize and publish focal points. If the bind is credibility, add commitment devices or third party enforcement. Do this on one page before any meeting. You will spot blind spots in your plan and avoid loud but empty tactics.

Case narrative one – an entry game that ends without a price war

A regional retailer eyed a crowded city market. Two incumbents had scale and loyal buyers. The retailer signaled patient entry by renting small space near underserved neighborhoods rather than opening a flagship downtown. Incumbents watched foot traffic data rather than cutting prices across the board. After six months the new entrant posted a price match on a narrow list of staples and focused promotions on categories where it had supplier contracts. Incumbents responded only in those categories. Everyone avoided a full war. Quiet signaling, limited commitments, and focused responses turned a potential spiral into stable coexistence.

Case narrative two – procurement and the winner’s curse

A public agency ran a sealed bid first price tender for a long maintenance contract on specialized equipment. Past contracts had been plagued by mid-term renegotiation because winners underbid, then demanded relief when true costs bit. The agency redesigned the mechanism. It split the contract into lots, required a common cost model with audited inputs, and used a payment rule that indexed part of the fee to verifiable input prices. It also adopted a two stage process that screened technical capacity before opening price envelopes. Under the new rules bids clustered near realistic costs and performance improved. The winner’s curse lost its sting because the design forced honest numbers up front and softened random cost shocks later.

Case narrative three – a repeated game with noisy signals

A manufacturer relied on three key suppliers. Quality issues had risen and trust was fraying. The firm rolled out a scorecard with three metrics that customers could verify at receipt. On-time delivery, defect rate by lot, and response time on rework. Contracts tied future order volumes to the score with a schedule that smoothed one-off shocks. After a learning period, two suppliers improved to keep volumes. The third failed repeatedly and was replaced. The repeated game with transparent signals and measured responses did what lectures could not. It aligned effort with payoffs.

A short operating checklist you can use tomorrow

Before you act, name the game and the players. Write down your best response to each of their likely moves. Delete anything that is dominated. Ask whether your threats are credible under backward induction. If you need honesty from others, build a mechanism that makes truth telling pay. If you need coordination, create a focal point and communicate it fiercely. If you want cooperation in a repeated setting, set clear triggers, monitor, and forgive after punishment so people can return to the high road. If the puzzle is private information, use signaling or screening to separate types. If the mess is a war of attrition, change the rules that reward waiting and limit waste.

Closing guidance that keeps strategy calm and sharp

Game theory does not tell you what to want. It tells you how choices interact. Use it to avoid grandstanding, to test whether your plan survives contact with a smart rival, and to build contracts and norms that reward good behavior without constant babysitting. Favor commitments you can keep over threats you will not execute. Favor designs that reveal information over speeches that beg for trust. Favor repeated fair play with teeth over one-off heroics. Do that and you will stop playing twenty small games on impulse and start running one well structured game where your team knows the rules and the likely outcomes. That is how professionals make strategy a habit rather than a drama.